The July 2012 debate on how long (or short) school uniform skirts should be aptly brought out Mutula Kilonzo’s bold and witty personality both as a politician and minister. As Minister for Education between March 2012 and February 2013, Kilonzo stood in defence of schoolgirls demanding to be allowed to wear miniskirts. “I am in total agreement with them. Why do you dress a schoolgirl like a nun? These girls do not want to be nuns; they want to be modern like Mutula!” he was quoted saying, and even went against the wishes of school heads and provisions of the Education Act without blinking. In fact, he vowed to push for a repeal of the Act, which he said had been in force since 1968, to ensure flexibility so as to provide “smart” uniforms for school girls – long enough to appease conservatives and short

enough to please the students.

Kilonzo served in three ministries during President Mwai Kibaki’s second term, namely Nairobi Metropolitan Development (April 2008 to May 2009), Justice, National Cohesion and Constitutional Affairs (May 2009 to March 2012) and Education (March 2012 to February 2013). He was a member of the Orange Democratic Movement-Kenya, which had entered into a post-election coalition deal with Kibaki’s Party of National Unity. The Ministry of Nairobi Metropolitan Development was seen as low-key and created more to appease political interests than to improve service delivery as most of its mandates were already covered by the Ministry of Local Government. His Assistant Minister was Elizabeth Ongoro, the MP for Kasarani Constituency, while Philip Sika was the Permanent Secretary.

Nairobi’s urban growth was based on a 1973 strategy until 2008, when the ministry under Kilonzo developed the Nairobi Metro 2030: A World Class African Metropolis, which was a five-year master plan aimed at transforming the Nairobi metropolitan area into a “world class” hub offering sustainable wealth creation and high quality of

life by the year 2030.

The plan was to upgrade Nairobi’s status to that of cities such as Cairo, Kuala Lumpur, Johannesburg and Lagos. It proposed the creation of the Nairobi Metropolitan Region, consolidating 12 local authorities and establishing a Nairobi Metropolitan Authority. The proposed metropolis would cover areas within a 40- kilometre radius of Nairobi, including the municipal councils of Thika, Machakos, Mavoko, Kiambu, Ruiru, Karuri, Tala/Kangundo, Kikuyu and Ol Kejuado.

Central to the plan was the development of regional and global service hubs for business, trade and finance, development of Nairobi’s tourism sector through investments in hotel and transport facilities (including a massive upgrade of the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport), and crime prevention. This would in turn spur development of industrial parks and facilities within the city, investing heavily in building modern infrastructure to improve access to electricity, water and sanitation utilities.

The transport master plan would effectively improve infrastructure and land use planning. Among the focus areas was an urban mass transit strategy that centred around high-occupancy buses and modernisation of the existing commuter rail network.

Kilonzo even oversaw the preparation of a bill to make the ministry legally independent from that of Local Government. Instead of amending the Local Government Act, he opted for a totally new act that gave the Minister powers over 13 councils, including Nairobi City Council. Had it gone through, councillors and mayors would have been given new names and portfolios.

Being a newer ministry meant that Kilonzo achieved little in the one year he was Minister. Then and even later, it was a ministry long on ambition but short on delivery. The closest it came to achieving one of its goals was November 2012, when the Syokimau-Nairobi commuter train was launched by the Ministry of Transport. Kilonzo was born to Wilson Kilonzo Musembi and Rhoda Koki Kilonzo on 2 July 1948. After high school he attended the University of Dar es Salaam to study for a law degree, and was the first student in the East African region to graduate with first class honours. He was not afraid of blowing his own trumpet. “I am one of the best lawyers this region has ever produced. I was the first East African to score a first class law degree. I was the best student at the Kenya School of Law… I am as good as you can get, and I charge as much,” he once said when challenged to account for his wealth.

It is easy to understand why he was retained by Kibaki’s predecessor, President Daniel arap Moi, as a private lawyer, and why he litigated many high-profile cases. In 2013 he was among a battery of lawyers assembled by the National Super Alliance to lead its presidential election petition. The petitioners won.

At the Ministry of Education, which he took over from Prof. Sam Ongeri, Kilonzo was known for cracking jokes and smiling even when situations called for a more serious demeanour. But he was also a workhorse – those who worked with him at Jogoo House, the Ministry of Education headquarters, say he was always focused on bringing change to the education sector. During his one-year tenure, he reportedly never took a trip abroad, choosing instead to delegate the trips because, he always said, he wanted his bills passed in Parliament first.

In his short stint at the ministry, Kilonzo brought about changes that transformed education in Kenya and will have a long-term impact for generations to come. For instance, the Basic Education Act that requires all parents to ensure their children are enrolled in school was passed under his watch, working with Patrick Olweny as Assistant Minister and Prof. Karega Mutahi as Permanent Secretary.

The law sets out stiff penalties for parents and guardians who fail to enrol their children in school. It also outlaws child labour and spells out necessary interventions. The legislation enhanced enrolment in schools, building on the gains of free primary and secondary school education introduced during President Kibaki’s first term in office.

Mutula also oversaw enactment of the Kenya National Examinations Council Bill that changed the way examinations were administered. The law prescribes tough measures to prevent cheating in examinations, with specific provisions for students, teachers and even parents.

A sneaky clause in the Bill also outlaws teachers’ strikes during national examinations. Under the Kenya National Union of Teachers, they often called for strikes just before exams as a way of arm-twisting the State into honouring their demands. The Teachers Service Commission (TSC) Act was also passed under Kilonzo’s watch. In June 2012, Parliament passed the Teachers Service Commission Bill 2012 which, among other things, required teachers to register afresh with TSC.

The new law also gave the commission powers to ensure that those in the teaching profession complied with the teaching standards prescribed by the Act, which in turn made TSC somehow independent, with minimal interference from the Ministry of Education concerning the hiring and promotion of teachers. The law sets clear criteria for the recruitment of TSC members, including a university degree in education, to eliminate canvassing for certain people to be appointed. The Minister said the TSC Act would bring radical reforms that would enable students to get high-quality education. He also implemented the ban on weekend and holiday tuition in primary and secondary schools during school holidays.

Other barely acknowledged achievements were the development of Sessional Paper No. 14 of 2012 on reforming education and training sectors in Kenya, and the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development Bill. Mutula Kilonzo Jr, Kilonzo’s son, described his father as “goal-driven and unbelievably ambitious”. So ambitious that as a little boy, the elder Kilonzo walked around the village where he grew up with his shirt unbuttoned to show just how tough he was.

When it came to his sense of humour, Kilonzo never missed a chance to poke fun at serious issues. For instance, when judges, magistrates and lawyers launched a quest for a new official dress code, Kilonzo said the colonial-era wigs and gowns had overstayed their usefulness. “Gowns and horse-hair (wigs) made lawyers look like witchdoctors,” was how he expressed his support for change.

Never one to shy away from speaking his mind, Kilonzo once described the current Constitution as “NGO-driven” that would be a nightmare to implement. His argument was that it was not easy to achieve affirmative action and gender balance using the Constitution. His ‘prophecy’ has come to pass as the two-thirds gender rule has proved to be a major nuisance, especially in the public service. Nonetheless, when he was appointed Minister for Justice, Cohesion and Constitutional Affairs in May 2009, replacing Martha Karua, he made an about-turn and took up the role of mid-wifing the Constitution. His Assistant Minister was William Kipkorir and Amina Mohammed was the Permanent Secretary.

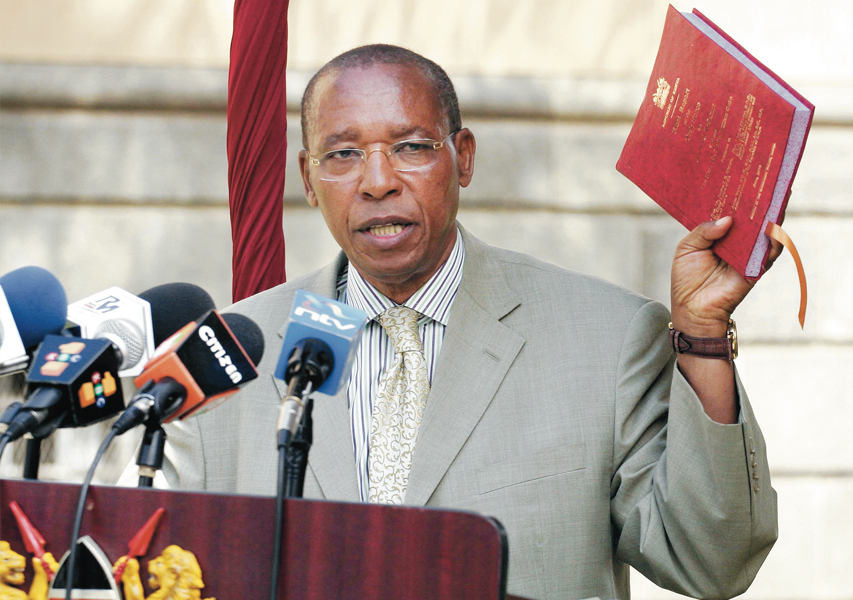

From a critic of the new Constitution, Kilonzo morphed into one of its fiercest supporters. The new Constitution was presented to the Attorney General on 7 April 2010, officially published on 6 May 2010, and subjected to a referendum on 4 August of the same year. It was approved by 67 per cent of Kenyan voters and promulgated on 27 August 2010.

At the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, just like at Jogoo House, his plate was full. There was the unfinished business of the National Accord, which had established the post of Prime Minister, and Agenda Four to address historical injustices, including establishment of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission and the emotive issue of Kenya withdrawing from the International Criminal Court.

An intelligent, articulate and seasoned lawyer, Kilonzo was one of the eight panellists who crafted the National Accord and was aware of the pending business of Agenda 4. Initially, he was among the strong proponents of a local tribunal to try post-election violence suspects, which was shot down. He argued it was the best way for Kenya, noting that “this country has got what it takes to address an issue such as the eruption of post-election violence through good legislative policies”.

While President Kibaki and Prime Minister Odinga were still dithering over forming a local tribunal, Kilonzo, in spite of being a Cabinet Minister, shocked many by publicly calling on the two leaders to resign. His argument was that the government would use the clauses in the Rome Statute to challenge the jurisdiction of the court and admissibility of the cases.

“What I was taught in criminal law is that in a country that respects the rule of law, it is far better for 100 guilty persons to be acquitted by a court of law than one innocent person to find his way to jail through irregularity,” he said at the time. Critics often argued that while Kilonzo had the right credentials to head the Justice and Constitutional Affairs portfolio, his past, which included being Moi’s legal adviser, robbed him of the moral ground to deliver reforms in a democracy. For years, he had defended a regime that placed obstacles in every path of a new Constitution until that regime – under the Kenya African National Union party – was removed by the ballot in 2002.

If Moi’s actions reflected the counsel he was getting from those around him, then Kilonzo cannot escape blame for some of the darkest moments in Kenya’s political history, which included detention of Moi’s opponents and the former President’s stubborn stance on multipartism and later, constitutional reforms.

All in all, Kilonzo proved to be an independent mind that was ready to stretch the rules and stick his neck out during his time in Kibaki’s Cabinet. In 2013 he became the first Senator for Makueni County but not for long. He died on 27 April of the same year at his Maanzoni farm in Machakos County – where he kept four lions, two cheetahs and rare eagles. His son, who had followed him into the law profession, succeeded him as the Makueni Senator.